MARINE SERRE

VOGUE RUNWAY: MARINE SERRE FW21 /

Marine Serre’s fall 2021 collection, dubbed “Core,” wasn’t heralded by a short movie or a runway show, not even a virtual one, but by a website, www.marineserrecore.com, which went live at her regular spot on the Paris schedule: 10:30 a.m. CET, on the first Tuesday of the city’s show calendar. Somehow, in the turmoil of our topsy-turvy world, there’s something reassuring about that; not that reassurance has ever really been part of the Serre narrative. She’s a fearless questioner—of herself as much as of anyone else—and a pragmatic doer. It’s easy to imagine Serre being energized by having to find her place, and that of her label, in the maelstrom in which we currently find ourselves. The website, then, is a chronicle of all that goes into her designs, and ergo her view of the world, as much as it is a reveal of her new collection. And because this is Serre, someone who always prefers to use a “we” over a “me,” Core is also a rather joyful and life-affirming celebration of family, friends, and community.

“Core means the core of the brand, in much the same way as the idea of the core of a computer,” Serre said during a preview a few days ago. “It’s all of the memory; how everything connects. Pragmatically,” she went on to say, “it’s been three years since we began. We’ve been doing a lot, being an extremely creative brand; we felt the urge to talk, ring the bell, raise the alarm, and reflect that in what we’ve created. This is maybe another moment. An opportunity to look at the interesting processes we’ve put in place; to really think about the garments and the materials we make them from—the transformation of those is really part of our creativity.”

The collection is essentially a blueprint of all that Serre has accomplished since she launched the label; the latest reimaginings of her archetypes. It’s also a pretty breathtaking and brilliant statement of what can be achieved in the space of three short years; what can emerge when you harness talent with a clear sense of purpose and convictions about what constitutes your values. “What I’ve always disliked about fashion is trends,” she said. “When you know who you are, you don’t need to change faces every morning.”

There are plenty of Serre’s repurposed silk scarves, draped around sinuous black dresses, which have been accessorized with talismanic metal belts and petite chain-strap bags, while other scarves have been worked into tunics and tees. Deadstock leather in shades of black, tan, and brown is graphically patched, with an anthropomorphic feel—the dynamic of how clothes move with the body was a big obsession here—into blazers with squared-off shoulders, biker pants, and jeans-style jackets, sometimes layered up with short dresses created out of antique tablecloths.

Meanwhile, moire silk, one of Serre’s signatures, makes an appearance cut onto jackets that are either sculpted close to the body or cut MA1 style, with a cool, easy sense of volume and the requisite zippered sleeves. It’s also been used for everything from short multi-pocketed skirts to baseball caps to small bags designed to be worn strapped onto the upper arms. And the now iconic crescent-moon-motif-embellished bodysuits and regenerated denim or else was mixed with more hybridity in the form of sweaters and dresses collaged out of upcycled knits. Also, can we also just talk for a moment about this collection’s omnipresent earthy brown palette? Perhaps it’s an aesthetic channeling of our collective desire to be outdoors, to be in nature, to be in the world, again.

All of this was shot on a terrific cross-generational cast of characters, kids included; a neat and effective assertion of the need for fashion to exist in reality, and to make sense of our lives. Now more than ever, we’re caught at the crossroads of function and fantasy, looking for pieces that can offer a way to somehow simultaneously head off in both directions without feeling tugged one way or the other. “It was interesting to revise what we’d already done,” said Serre. “Basically the goal was to bring more real life to our design process, to bring garments into daily life.” Her solution was to ask the team to try things on, give their feedback, then modify to make everything more relatable. The world around the label features in other ways too on the new website. You can click on different aspects of the collection—“regenerated denim” or “regenerated silk scarves”—and be taken to mini documentaries outlining how the company uses those fabrications; a clever and thoughtful way to demystify the design process.

The website also houses a charming series of fly-on-the-wall photographic depictions of those within the extended Serre label family, wearing a few of the pieces, and engaged with the humdrum realities recognizable to every single one of us. “Cooking, spending time with your mother, in the garden, playing with your dog...pleasures which are simple,” said Serre, describing the scenes. “Fashion has always been about a dream, and I don’t like that. Here, fashion is the last thing you see. What you see first are the people.” Serre’s thinking about the site is akin to the way she thinks about her designs. Visit, spend time, come back, visit again, get to know what something means and what it stands for. Nothing should ever be fleeting, or disposable, gone in the blink of an eye.

By Mark Holgate

PURPLE MAGAZINE: MARINE SERRE /

imagining a post-apocalyptic time, the rising star of paris fashion is making upcycling the new standard while pushing the creative possibilities of sustainability

interview and portrait by OLIVIER ZAHM

OLIVIER ZAHM — What is your relationship with nature?

MARINE SERRE — I grew up in the country. Until I was about eight years old, I lived in a small city, Brive-la-Gaillarde. Then my parents felt they needed some space and freedom, and we moved to an old farmhouse in a hamlet of five houses in the Corrèze region, with four families, a dog, and nature all around us. I grew up in a microcosm, with a direct relationship to nature. As soon as I’d get home in the evening, I’d go for a stroll in the forest.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you have a lot of freedom as a child?

MARINE SERRE — Yes, and great bodily freedom as well. You’re unaware of it at the time. Only later, when you’re living in Paris and start to miss it, do you realize what you had. At the same time, I really love cities, but only because I know I can get away. In the summer, I’ll often head to the mountains for three weeks at a time. I’ll just up and go with nothing: just my bag, some water, a pair of socks, a pair of shorts — stuff like that. They’re really memorable excursions — seven hours of hiking per day. At every moment, you’re face-to-face with a world much larger than you. It’s really a question of scale — between nature’s vastness and your size as a human being.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You’ve incorporated an environmental ethic into your brand. Has that always been part of your world?

MARINE SERRE — For me, it’s very natural. My whole collection for my fourth year at La Cambre [an art and fashion school in Brussels] was recycled. But it wasn’t something I put into the marketing. It’s a way of working and, for me, a part of the process. Only recently have I begun speaking about it openly.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, you were already recycling garments for your student collections?

MARINE SERRE — Yes, or fabrics I’d come across. Tarps from worksites made into trench coats, for example, or bathroom rugs or felted wool blankets made into coats. It was an economical approach because I was short of money for producing my collections. It made no sense for me to go to a fabric vendor and buy new fabrics. It made more sense to take a fabric that was already in daily use, with its own value, identity, and history.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Materials that already have a history…

MARINE SERRE — Yes, but what I really love is transforming those materials. When I was young, I spent a lot of time in secondhand shops. My grandfather runs a secondhand shop, and he passed on a certain relationship to objects — to the value of objects of a certain quality, and also of objects of no value. I made a piece like that last year, a coat covered in key chains. They were worth 10 cents apiece, but when you put them together, a transformation takes place.

OLIVIER ZAHM — We consume too much, produce too much — too many garments as well. It’s a contradiction inherent to fashion, which turns on the renewed desire for change. How do you deal with that paradox?

MARINE SERRE — I transform it. I take what’s already there, and the only energy I use is my own and my team’s as we rack our brains to make you want to wear the garment tomorrow, to make it desirable.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Why create a new fashion brand in a world that’s already saturated with them?

MARINE SERRE — I wanted to be useful, not to do things gratuitously, to try to be coherent. I created my brand because I wanted to make a small contribution to the necessary transformation of the world we live in.

OLIVIER ZAHM — A world headed for doom.

MARINE SERRE — It’s crazy.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you think this is unique to your generation?

MARINE SERRE — People are finally ready. When Martin Margiela worked on recycling, fashion consumers were less ready than they are today to deal with a collection designed with these ideas in mind. With everything that’s happening all around us, we have to find some other way to think and work.

OLIVIER ZAHM — In your view, can fashion and fashion designers steer their audience toward the necessary changes?

MARINE SERRE — I think so, yes. But it’s not as if I believe that I myself can do it! I’m hoping to build an ecological brand, but I’m very realistic about what’s happening today. We’ve only suffered defeat until now. Real failure. Even if it’s true that we mustn’t get discouraged — because it’s important to stay enthusiastic and lighthearted, and not lose sight of what you want to achieve.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Unfortunately, it might only be when things get dramatically worse that we finally react.

MARINE SERRE — Yes, and people today see it almost as a duty, but I don’t. I see it as an ordinary thing. It’s neither a duty nor a responsibility: it just makes sense. Once we decide to maintain a certain connection with nature and with life, if we don’t want to end up in a bubble all by ourselves, then we have to consider the trees around us, the air around us, and what happens between us all.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Could you explain what you mean by upcycling?

MARINE SERRE — For me, upcycling, unlike recycling, means taking garments at the end of the chain, before they’re destroyed, and transforming them, raising their quality and making them into unique objects from a fashion perspective.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And you have to sort through tons of clothing?

MARINE SERRE — Tons and tons of clothing! A small part of used clothing goes off to vintage shops, but a lot is burned or sent to Africa or sometimes stored without any specific plan. You have these mountains of plastic bags you have to sort through, while thinking, “What can I do with all this?” The transformed item, clearly, had better be perfect. I’m intransigent on that point. I want every one of my pieces to be impeccable. It’s a crazy feat interms of production. No one has ever managed to do it working with a factory, on a large scale.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Was Martin Margiela a precursor of this?

MARINE SERRE — Yes, absolutely. I was lucky enough to work for the Margiela fashion house when Matthieu Blazy was the creative director, before John Galliano. It was tremendously inspiring to see how the house would go about transforming vintage clothes. Of course, I studied in Belgium. Recycling is part of the fashion culture in Belgium, and I was able to round out the year by making a trench coat out of tarps. It wasn’t really a problem. [Laughs]

OLIVIER ZAHM — You’ve refined your creative relationship to recycling, pushing it toward experimentation.

MARINE SERRE — With the Red Line, a more experimental line of couture, I can take things further and have some fun. I think certain people have a lot of fun wearing my clothes. At the same time, though, what you wear every day — your wardrobe, your daily vocabulary — is essential. I think we all know that these days, but we don’t want to look like a clown when we’re on the street. So, apart from the couture pieces, the daily vocabulary and the everyday aesthetic can be fascinating.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Is that the biggest challenge?

MARINE SERRE — We spend a lot of time working on that. The factories we’re using today understand what we’re trying to do, but at the same time, the actual manufacturing is complicated because they’re not used to it.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You have to train the factories?

MARINE SERRE — Exactly.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How many different lines do you have?

MARINE SERRE — We’re working on four lines. The Green Line is exclusively based on upcycling: nothing but garments that have been transformed and become something else. We have jeans, leather, silks, wools. Our prices are very high for the moment because it takes a while to make our raw materials and work on them, so we operate almost at a loss. We’re looking for ways to make production profitable and offer affordable clothes. How do you offer upcycling at an affordable price? On a few items, we can manage it— for example, with jeans, we have to open the seams on the sides, remove the zipper, resew everything from the inside…

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, you develop original production techniques.

MARINE SERRE — Absolutely.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And that’s something Margiela never took very far. Margiela was more about the deconstruction of clothing — garment after garment. He didn’t go too far with production.

MARINE SERRE — Right. I myself am looking not to deconstruct, but to transform. This enables me to create a desirable product, if you will, with the proper proportions. Because in the end, it’s also a matter of the silhouette.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What are the other lines?

MARINE SERRE — In addition to the Green Line, we have the Red Line, which is more couture, more artisanal, where I can really let myself go creatively and collaborate with artisans. The latest piece you’ve probably seen, for example, is the dress with the white drape, which is made of recycled T-shirts and has become a haute couture dress, with a strapless brassiere on the inside. I really see it as a redcarpet dress.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What are the two others?

MARINE SERRE — There’s the White Line, which is really the everyday wardrobe — woolen suits, for example. And price is important to me because in the stores today, designers often end up with very expensive items that are not worth the price. For me, it’s super-important to find the right price. We try to keep an eye on it all the way down the chain.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Just to wrap things up with your lines, is there another line after the White Line?

MARINE SERRE — The fourth is the Gold Line, which is rather hybrid. All the pieces I’ve made are a mix of vocabularies — between jerseys and moirés, for example. The Gold Line is really experimental — reflecting the most artisanal or the freest side. How can I make the wonderful fabric on this chair into a wonderful pair of pants to replace your jeans? It’s also about opening the way to unknown materials and to collaborations. It’s about developing an as-yet-unknown fashion vocabulary. It’s the most fashion-oriented line!

OLIVIER ZAHM — Let’s go back to the idea of sustainable fashion. I speak in terms of cosmic awareness, if we can call it that. The word “environmental” is no good.

MARINE SERRE — “Ecological” has become old hat, too. It’s been used so much and become so commercial. Now all brands have a “green line.”

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s marketing, and overproduction is still a problem.

MARINE SERRE — That’s why I insist that the Green Line is nothing but upcycling. Only with the White Line, which is more or less a normal line, do you have organic cotton, recycled materials, and so on.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You said you’d gone to Copenhagen. When you look around, do you see young designers making similar moves?

MARINE SERRE — Yes. I think it’s really starting to catch on. There are millions of things I don’t know. We’ve just moved to the north of Paris, into much bigger premises, and I’m more or less trying to do as much as possible in-house. That way, I don’t resort to air freight or sending any packaging, and all the transformation is done right there. I find that very stimulating. You have the real energy of the people who are present, creating the piece with you. It generates group energy as well.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The wonderful thing about you, I find, is that you’ve made this commitment without compromising your creative ideal. Your creative ambitions are intact.

MARINE SERRE — Things start there. That’s the beginning.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Because designers will often focus on design and the effect their piece is going to have. They won’t abide by any limits.

MARINE SERRE — I see myself more as being at-the-service- of, you see? I feel that I’m more at everyone’s service, even if that seems a bit odd.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Without losing your creative ambitions.

MARINE SERRE — Right. But with a very clear vision of it. Sometimes I drive my team to desperation because I’m radical! Today we’ve lost clarity, vision. There’s so much information about everything that we’ve lost our way…

MARINE SERRE: REGENERATED Intervened T-Shirt /

VOGUE: Marine Serre Discusses Her Spring 2020 Collection /

“After the Apocalypse…Maybe You Try to Make a Wedding Dress”

By Steff Yotka for Vogue

Marine Serre does not mince words. The designer called her Spring 2020 collection “Marée Noire”—French for oil spill—and set her show on a wild hillside near the Hippodrome de Paris in the drizzling rain. A cast of real-world models walked over a swamp on a runway wrapped in black to look like oil. The internet went wild for the second dude out, a middle-aged man with hollowed-out cheekbones and a grimace that could put Willem Dafoe out of business. Days later, in her studio on the outskirts of Paris’s 19th arrondissement, Serre reflected on the potency of her set: “If it had been roses,” she said of the brush around the runway, “I wouldn’t have had the show there.”

Serre’s willingness to add a little aggression, maybe even viciousness, to her runway presentations is part of what catapulted her to the international stage as one of fashion’s more provocative young designers. Her intensity is matched by a deep thoughtfulness: Serre is a passionate and knowledgable environmentalist and has, since launching her brand in 2016, worked dutifully to upcycle 50% of her garments, each year working to increase that number. That all wouldn’t matter, of course, if she wasn’t a deft tailor and draper, working out the problems of how to turn used neoprene wetsuits into Grecian-tinged dresses or hotel towels into miniskirt suits. What materials Serre and her atelier have, they use, and when they run out, production is over. “That’s the thing about upcycling, we don’t have to make too much. And when the [resources] stop, you don’t force it,” she said.

It’s not just the corseted dresses made from bed sheets, the granny scarves draped into bridal-worthy finery, and the metal jewelry strung together from seashells and ocean-weathered soda cans that Serre and co. have recycled either. In the studio, nearly every object and every surface comes from somewhere else. The shoes and bags are displayed in a meat case spliced with a vintage dresser. The pipes guests sat on during the runway show have since become plinths for jewelry. Chairs and tables scattered throughout are Frankenstein’d; motorcycle wheels combine with mid-century tabletops, and hand trucks serve as the back to dinette chairs. Just before the Vogue team arrived, A$AP Rocky had passed through, trying to buy up every piece of furniture while picking out a Marée Noire trench to wear out in Paris that night.

Maybe the furniture will go up for sale soon. Maybe Serre will launch a program to buy back her previous season garments. Maybe she’ll even let customers send in their unwanted wares for her to transform into something new. The potential of what Serre can rebuild, recycle, and recreate seems endless. But for now, she’d like to reveal a little bit of her process and some of the story of her Spring 2020 collection. “After the apocalypse…maybe you try to make a wedding dress,” she said, nodding at pieces mashed up from scarves, blankets, wetsuits, and tablecloths.

MARINE SERRE: FW19 Radiation /

In a not-so-far future the distinction between culture and nature is erased from memory.

Welcome to Radiation, a virtual playground of Marine Serre’s pluriverse, a hybrid utopia-dystopia built to simulate futurewear in post-apocalyptic conditions.

This short film from MARINE SERRE is a collaboration with the tech-art video couple Rick Farin and Claire Cochran, who specialise in the rendering of speculative futures within video game engines.

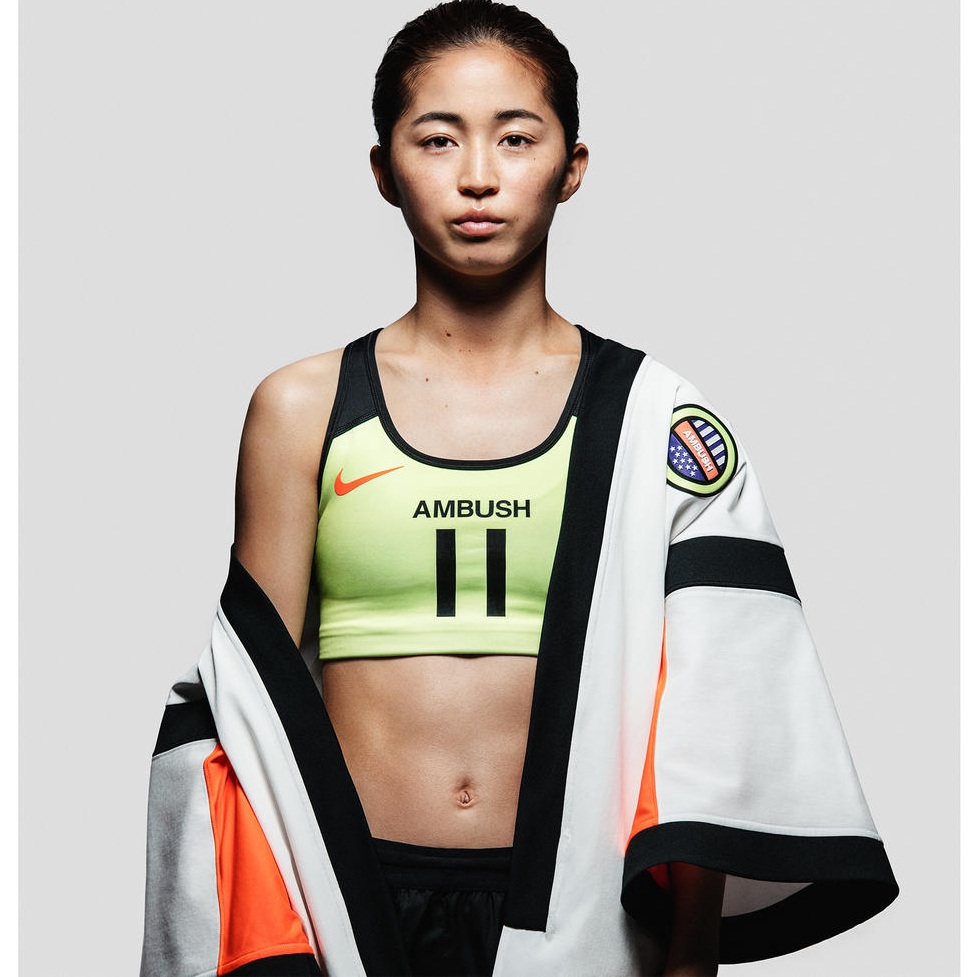

NIKE Collaborations: Yooh Ahn and Marine Serre /

Yoon Ahn and Marine Serre Celebrate the Football Shirt

In sport, the jersey is a garment that at once supports and celebrates brilliant performance.

For athletes, it serves a utilitarian purpose — the jersey is a tool for their crazy dream. For the fans, the jersey serves to support their favored team and, ultimately, their community.

As the world readies for play in France this summer, Yoon Ahn, Christelle Kocher, Erin Magee and Marine Serre transform the jersey in their vision, proving that while a jersey need not take a standard form, it can become a standard reminder of the unifying power of sport.

Each designer has also matched a bra with their jersey. Here they describe the intent behind their respective concepts:

Yoon Ahn’s Nike x AMBUSH® jersey shines a spotlight on the diversity and culture that is celebrated on the international tournament stage.

“My Nike x AMBUSH® jersey is a unisex hybrid football jersey inspired by the Happi coat, a traditional Japanese straight-sleeved coat. I chose the Happi coat because, although we are celebrating the tournament and the incredible female players, I believe it is just as important for the fans, for everyone to have a universal piece to celebrate in.”

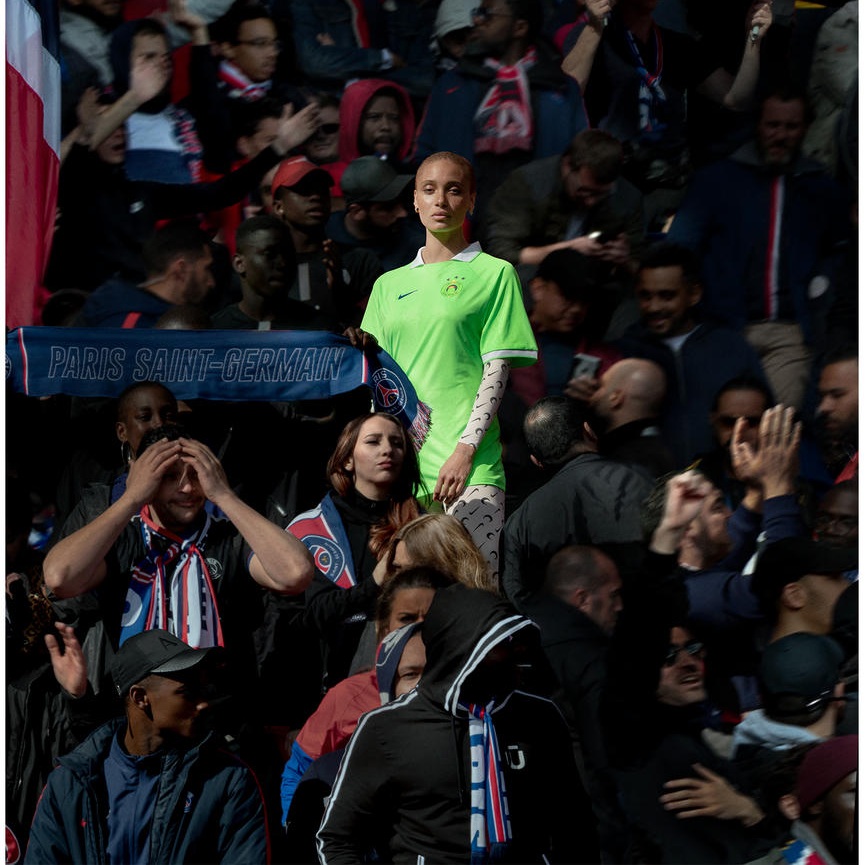

Serre presents a slender, articulated jersey designed to be worn over a printed body suit.

“The focus of my designs is always hybridity and adapting to daily life. It’s important to create a purposeful line that makes a female feel good without compromising the style.”

PURPLE Magazine: Marine Serre /

“After the decade of Mugler and Montana, Paris mainly welcomed

young designers from elsewhere.

Today a new generation is finally emerging.”

OSCAR HELIANI — Why did you settle in Paris?

MARINE SERRE — It wasn’t really planned. It just happened. I was living in Brussels — a wonderful city, by the way — but I was starting to get bored. When I got this job at Balenciaga, I found a tiny studio in Paris. You know how expensive the rent can be! On the whole, I’m more linked to people than to cities, but I do enjoy the melting pot of people and the huge opportunities that Paris offers.

OSCAR HELIANI — What is it like to start a business here?

MARINE SERRE — I never tried to do business in another city, so I don’t know what it’s like elsewhere. I could have chosen to start the brand in the Netherlands because my partner is Dutch, but, legally speaking, it was easier to do so in France, although I consider the brand an international one. I’m very happy with this decision, and I intend to stay in Paris and let the brand grow here.

OSCAR HELIANI — Do you feel a resurgence in the French capital?

MARINE SERRE — I do. I keep receiving job applications from people around the world willing to move to Paris and work in fashion. I’m not sure it would be the same in Lisbon. Who hasn’t dreamed of the Parisian way of life? Paris is a big city, without being huge. It is built in such a way that almost everything is happening in the centre. People usually complain when you invite them somewhere far away, and they pretend that the transport network is bad, and so on. I have to disagree. Major things are happening everywhere, especially in the nearby suburbs. Before settling here in the second arrondissement, we searched for offices in Aubervilliers [a suburb north of Paris] but couldn’t find anything big enough. We’re moving soon for something bigger, and it happens to be in the north of Paris.

OSCAR HELIANI — Do you see any disadvantage to moving to Paris?

MARINE SERRE — The rent is so high that you’re stuck in small spaces, without any possibility of expanding your business or even your team.

OSCAR HELIANI — What is your favorite neighborhood in Paris?

MARINE SERRE — I live near Porte de Clignancourt, and I really like it. Both the 18th and 19th arrondissements are cool for hanging out, taking a break, or biking.

OSCAR HELIANI — What is one of your secret places in Paris?

MARINE SERRE — Well, it won’t be a secret anymore, but I really enjoy going to Mala Bavo, a Kurdish bar in the Rue Saint-Denis. The mood there is nice, and people are totally relaxed. My team and I usually watch a soccer game, and I learned a traditional Kurdish dance the other day.

OSCAR HELIANI — Is there any link between your collections, the city of Paris, and French fashion?

MARINE SERRE — My collections have references, but not to Paris or French fashion, which, for me, mainly concerns the established houses.

OSCAR HELIANI — But isn’t casting Amalia Vairelli, Yves Saint Laurent’s iconic Somali model, for your “Hardcore Couture” show also a way of paying homage to French fashion?

MARINE SERRE — Not only does Amalia evoke French couture, but she’s also definitely a killer with her sharp hard-core attitude on the runway. I first got in touch with her because I love the way she walks, but as I got to know her, I discovered what a wonderful person she is. She understands the whole design process and knows how a garment works. There aren’t models like her anymore. If that’s what you mean by French fashion, then I’m definitely buying it!

OSCAR HELIANI — What is your approach to casting?

MARINE SERRE — The casting for my “Hardcore Couture” show took me more than three months. Seventy percent of the models were nonprofessional. I met each and every one, listened to what they had to say about feeling good wearing the clothes and being confident when walking the runway. Obviously, I’m not changing models every season. There is no expiration date, so why would I do it?

OSCAR HELIANI — You presented your first show at Calentito, Blanca Li’s dance studio in the 19th arrondissement, and your second show at the Jardins d’Éole, an outdoor setting in the same area. How do you choose your venues?

MARINE SERRE — For my “Manic Soul Machine” collection, I wanted a square space that had a raw concrete feeling without being too underground. When it comes to venues, the challenge is to find an affordable space matching all your criteria. The best solution is to reach a compromise, finding a location outside the area where all the fashion shows are held. Besides, I liked the studio’s neighborhood, and I used to practice contemporary dance myself, so I may have been unconsciously attracted to Calentito. The whole collection was related to movement: models were asked to walk in a choreographed way, and the fabrics were flowy, which was a perfect match. While working on the “Hardcore Couture” collection, I was walking one day with my sister on this long bridge under a beautiful sky, and it hit me: “Isn’t this the perfect spot for a show?” A huge catwalk crossed by all types of people: a guy on his bike, another one playing music, men exercising, and people taking a Tai Chi class. The day of the show, people in the garden could also watch the collection. I wanted everyone to be part of this experience. The only reason I decided to show outfits on men and children (who, by the way, walked with their real parents) was that I was seeking some realness. People never complained that these two locations were too far away.

OSCAR HELIANI — How would you describe your style?

MARINE SERRE — I don’t think of myself as an artistic director. I try to have a global vision for the brand, from design to production and merchandising. As fashion is always evolving, I would rather refrain from any definition of identity or style and avoid getting stuck there. But I can give you a hint about what I’m trying to achieve. I want to bring to my customer, who is between 18 and 65 years old, a very shaped silhouette with all the means to be free. I focus on proportions, and I pay close attention to shoulders. But if a woman wearing my design feels uncomfortable, this means I missed my goal. The women in my team and I try on all the pieces to ensure that everything is comfortable.

OSCAR HELIANI — Are you suggesting that other designers are not always down to earth?

MARINE SERRE — I have no comments to make about other designers. I would add, though, that we have to find a balance between the designer’s dream and the reality of the garment. Dreaming is important, but one should keep a sense of irony, too.

OSCAR HELIANI — What are some of your most popular designs?

MARINE SERRE — Our “Green Line!” It was really challenging to design. Having a limited quantity of fabrics, I had to think constantly about whether we had enough upcycled scarves to go into production. But the added value of this line is huge, and every piece is different from the others. The customer understands the time we spent collecting the fabrics, assembling and finishing the garment. And, above all, the final product is nice. I don’t want the customer to look like a clown. When we started the “Green Line” for the “Manic Soul Machine” collection, I didn’t tell anyone about the process. I wanted to check if people really liked it or not, without having in mind that it’s upcycled fabrics, so they should like it. We did it again for the “Hardcore Couture” collection. The “Green Line” pieces were the best-selling ones. It was the perfect time to launch this line. I’m lucky because five years ago, I’m sure that it wouldn’t have been as successful.

OSCAR HELIANI — If you had one fashion statement, what would it be?

MARINE SERRE — Keep your eyes wide open.

By Oscar Heliani for Purple Magazine