Ultimately, Martine is inspired by those people, too. She’s always been adept at reworking garments that are already there, finding inspiration in the kind of things that her friends might be wearing, or remembering the garments of her older brothers or cousins and their friends, and drawing rose-tinted inspiration from the wardrobes of those slightly older, slightly cooler people we looked up to when we were younger. The way one of them might layer together something as simple as a jumper and a shirt and reveal something new about both, how a jacket could be tied around the neck maybe, or what shoes they wore with what jeans, or the clash of formal and informal in the way clothes are worn. Tracksuit bottoms with loafers, maybe, or cycling shorts with a silk shirt. The rare beauty of the coat pulled from the obscurity of a charity shop rack that doesn’t quite fit right but it’s wrong in an amazing, unique way. And all those emotions tied to the clothes we wear find their way into Martine’s designs.

Her personal history provides much of the inspiration for what she does. Situated in it are a few foundational myths, like clubbing at 14 in Vauxhall, or dancing on Clapham Common in the dawn light during the Second Summer of Love. But within this specificity there is a universal appeal, because there is a universal nostalgia for a moment of belonging, for something bigger than ourselves, for community and curiosity. Martine’s shows and clothes are about that moment of belonging, bringing people together. It’s about situating the magical nature of fashion – its transformational abilities – in reality.

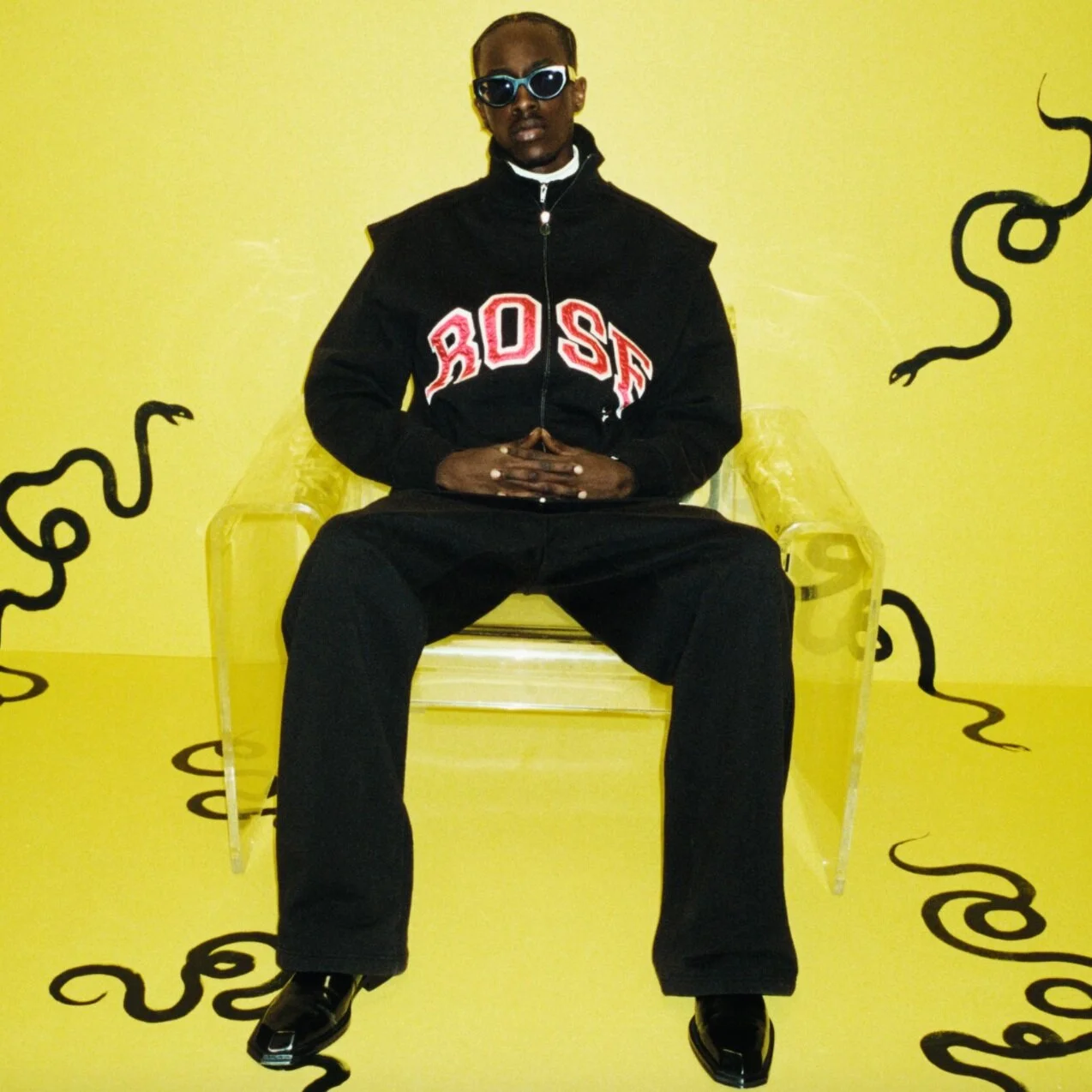

So Martine’s clothing is about magical realism in that sense. Or maybe we can call it the subcultural baroque in the way that it’s about elaboration and symbiosis and mutation. It’s about how that ordinary garment, that pair of trousers, that jacket, can hold so much heroic weight, so much mythology. Then Martine takes that sartorial mythology and twists it around. “I guess I like the familiarity,” she says, of taking a garment apart and rebuilding it. “There are rules and parameters that come with familiarity and archetypes that really resonate with me. The garment must stay recognisable which gives me specific parameters to play with. That’s what first attracted me to menswear – there’s certain rules and I like the challenge that they bring. And applying this to something as iconic as a football top, for example, which is not only a garment that everyone knows but one that people have an emotional attachment to, gives it even tighter parameters for recreation. It makes even more interesting.”

Which is what I mean by describing Martine’s clothing as a kind of magical realism, these clothes which we know so well – the trench coat, the tracksuit bottom, the loafer etc – that are inflated, made heroic, made magical, without losing their reality. And fashion is usually so exclusionary, and that is part of its magic too, but there’s a confidence in letting people into your world, a confidence in what you do in allowing so many different people to take to it and become part of that world. It comes back to that idea of community. And ultimately, that’s about people (some of whom we interviewed below, people Martine works with, her collaborators, friends, accomplices, fans, models) and Martine Rose is the people’s designer.